Trauma responses are normal reactions to abnormal situations.

Experiencing trauma is common, but its effects are often very long-lasting. Trauma refers to any distressing event that causes emotional, psychological, or physical harm. Research suggests around 70% of adults in the U.S. have been through at least one traumatic experience.

It’s important to understand trauma itself is not a disorder, even though it can negatively impact mental health. Trauma throws off emotional and functional balance, often derailing psychological well-being. Common effects include feeling emotionally numb, anxious, irritable, disconnected, or overwhelmed.

So, while trauma is not a disorder, it’s often at the root of diagnoses like PTSD, Acute Stress Disorder, anxiety, or depression. In other words, trauma is often the root cause of a bunch of disorders. But the trauma itself is not classified as a mental illness. In the workplace we do our best to support people with trauma: we don’t want to retraumatize them, and we want to help them build resilience. We want to show up with compassion and curiosity versus writing someone off as trouble, etc.

In most work environments, being trauma-informed means recognizing trauma’s widespread effects while understanding it differs from clinical diagnoses, so we can compassionately support colleagues, recommend EAP resources, loop in HR when appropriate, while also staying within our scope of practice.

The concept of a trauma-informed approach emphasizes the importance of providing support and assistance to individuals who have experienced trauma. We strive to be sensitive, compassionate, and empathetic . The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA’s) 4R’s approach is well-established and effective. The 4R’s are:

- Realization: Recognize the prevalence and impact of trauma. Understand that trauma can have long-lasting effects on individuals and that it may manifest in various ways, both overtly and subtly.

- Recognition: Identify the signs and symptoms of trauma. Be aware of the potential behavioral, emotional, and physical indicators of trauma in individuals, as they may present differently in different people.

- Response: Respond in a compassionate and supportive manner. Create a safe and non-judgmental environment where individuals feel heard, validated, and understood. Respond to their needs with empathy and respect.

- Resist re-traumatization: Ensure that practices and policies are in place to prevent re-traumatization. Create trauma-informed systems that prioritize safety, autonomy, and the well-being of individuals. Foster an environment that promotes trust, collaboration, and respectful communication.

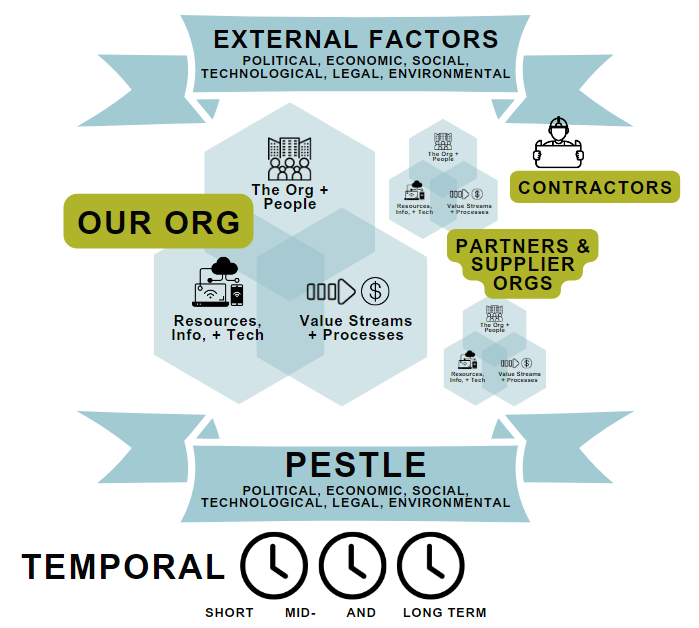

It’s important to note that while these 4R’s provide a helpful framework, trauma-informed approaches are not implemented as a “one and done” event, but rather this is embodied by our hearts and by the heart of our organization as well. It requires ongoing education, self-reflection, and a commitment to creating environments that foster healing, resilience, and empowerment for individuals who have experienced trauma. This lens would be applied to our entire value delivery system — all of the dimensions that relate to our workplace (and beyond… as I will address later in this post). We need to delve deep into each dimension to make sure we are connecting the dots on truly adopting a system-wide trauma-informed resilience (TIRO) approach.

#1 Realization

Realization has a few components: prevalence, impact, and how trauma manifests.

(1) Prevalence

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study published in 2020, nearly two-thirds of adults in the United States have experienced some form of adverse childhood experience (ACE) such as abuse, neglect or household dysfunction. The study revealed that 60.9% of respondents reported at least one ACE and 15.6% reported four or more ACEs. Furthermore, the study found higher prevalence of ACEs among certain demographics such as women, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with lower incomes and less education. This underscores the urgent need to address trauma and ACEs to prevent long-term adverse health outcomes.

There are many different categories (and subcategories) of trauma, and you can read about some of them here.

Some reputable sources that often publish research on trauma and ACEs include:

- Compassion in Action (501c) – ACEs stats

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – The CDC provides valuable information on ACEs, trauma, and their prevalence. Their website contains data, research publications, and resources related to these topics. (Website: www.cdc.gov)

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) – The NIMH conducts research on various mental health topics, including trauma. Their website offers information on the prevalence of trauma and ACEs and provides access to relevant research studies. (Website: www.nimh.nih.gov)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) – SAMHSA is a government agency that focuses on behavioral health issues. They publish reports and resources on trauma-informed care and may provide statistics on trauma and ACEs. (Website: www.samhsa.gov)

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) – The NCTSN is a collaboration of academic and research institutions dedicated to understanding and treating childhood trauma. They conduct research and publish resources related to trauma and its prevalence. (Website: www.nctsn.org)

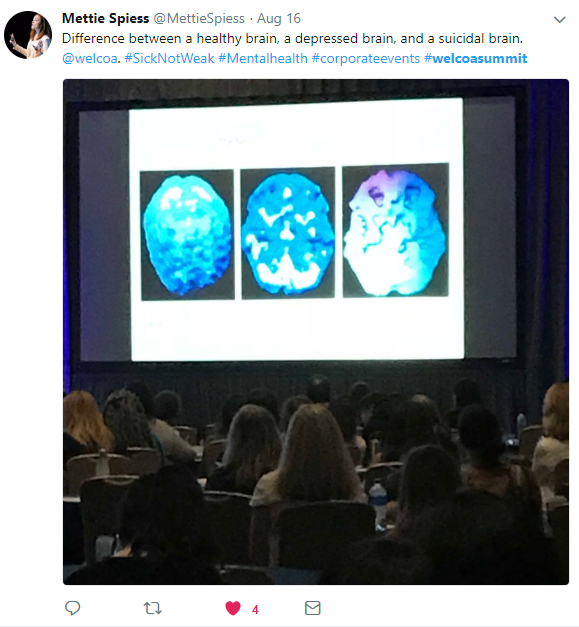

- A World Without Suicide offers excellent programs from Mettie Spiess.

(2) Impact

Research has shown that trauma can have a significant impact on society. Traumatic events such as ACEs, natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and war can lead to physical, psychological, and social consequences that can affect individuals, families, and communities.

In terms of physical consequences, trauma can result in injuries, disabilities, and chronic health problems. The psychological impact of trauma can lead to mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. Social consequences can include disrupted relationships, loss of trust in institutions, and increased rates of crime and violence.

Trauma can also have a long-lasting impact on children, with research indicating that those who experience trauma are more likely to have poor academic performance and behavioral problems. The impact is long-lasting because trauma encodings are ‘meant’ to be indefinite.

Before a trauma encoding is installed in the membrane of a nerve cell, you can see the typical phospholipid bilayer at left. When we are rattled by events that meet the criteria to install a trauma encoding (like adding a little antenna), we see really fast gamma waves sweeping through the brain:

Fast learning occurs under times of great threat and great novelty. This entails the swift install of receptor channels (these will serve as lookout antennas for us):

Encodings are installed, not just for the threatening content, but for anything and everything that may be useful to remember. This is not an episodic memory (story-based) this is called felt sense memory. The “Dear Diary…” story-based memory gets stored in a different part of the brain than the memories of the sights, sounds, etc do.

By remembering everything (and more) about whatever hugely rattled us, our brain is ready with a lightening fast alert (e.g. a flooding of emotion, body sensations, etc) should something similar happen down the line. These felt sense memories are literally encoded (installed as ion channel receptors) in the relevant regions of the brain, like little antenna. These ion channels will respond many times quicker than the blink of an eye if they pick up on similar sights, smells, etc.

The fast learning response that installs trauma encodings:

What does it take for trauma to get encoded in the brain? Watch this:

The imprints of trauma are also passed down from generation to generation. The epigenetic component of trauma refers to the alterations in gene expression caused by environmental factors.

Studies have shown that traumatic experiences can leave a lasting imprint on the epigenome, which influences the way genes are expressed. For example, a study by McGowan et al. (2009) found that childhood abuse was associated with increased DNA methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene, which has been linked to stress response and psychiatric disorders.

Another study by Yehuda et al. (2016) found that epigenetic changes in genes related to stress regulation were associated with trauma exposure in veterans.

These findings suggest that trauma can have lasting effects on the epigenome, which may contribute to the development of mental health disorders.

Overall, the impact of trauma on society is significant and can result in a range of negative outcomes. It is important for individuals and communities to have access to support and resources to help cope with and recover from traumatic events.

#2 Recognition

How Trauma May Manifest in Children

Children who have experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and trauma may exhibit a variety of overt and indirect behaviors and symptoms. Overt examples may include aggression, anxiety, depression, difficulty with self-regulation and emotional control, hyperarousal, defiance, and withdrawal from social interactions. Indirect indicators may include physical complaints such as stomach aches, headaches, and fatigue, sleeping disorders, poor academic performance, and a lack of interest in activities that used to be enjoyable.

ACEs and trauma may also impact a child’s ability to form and maintain healthy relationships with peers and adults. They may struggle with trust and attachment, find it challenging to communicate effectively, and have difficulty managing conflict and making positive choices.

Other common manifestations of ACEs and trauma in children can include feelings of shame and guilt, difficulty with processing emotions, and a sense of powerlessness or helplessness. These symptoms can have long-lasting effects throughout a child’s life, impacting their mental health, cognitive development, and physical well-being.

Overall, it is important for parents, caregivers, and educators to be aware of the signs and symptoms of ACEs and trauma in children, so they can provide the necessary support for healing and recovery.

How Trauma May Manifest in Adults

Overt ways that ACEs and trauma may manifest in adults include symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance. Additionally, survivors may struggle with anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders. Physical health problems, such as autoimmune disorders, chronic pain, and fatigue, may also arise. Indirect ways that ACEs and trauma may manifest in adults include difficulties with relationships, including trust issues, difficulties with emotional intimacy, and a tendency to overreact to perceived threats. Survivors may also struggle with self-esteem and feelings of worthlessness, which can lead to self-destructive behaviors such as substance abuse or eating disorders. Finally, survivors may be more likely to experience challenges in employment, financial stability, and housing security.

How Trauma May Manifest @ Work

Overt ways that ACEs and trauma can manifest in the workplace may include frequent tardiness or absences, difficulty concentrating, irritability, outbursts of anger, and poor interpersonal relationships with colleagues. Indirect ways may include decreased job satisfaction, decreased productivity, lack of motivation, and feelings of hopelessness.

These behaviors and attitudes are often connected to individuals’ past experiences of adversity and can have a significant impact on their work performance and career advancement. Moreover, they can also contribute to a negative workplace culture and can trigger or exacerbate conflicts with co-workers or supervisors.

Ultimately, addressing ACEs and trauma in the workplace requires a multi-faceted approach that includes a supportive organizational culture, access to mental health resources, and training for managers and colleagues to recognize and respond to the symptoms of trauma effectively.

Dysregulation (at any age)

In the context of trauma, Polyvagal Theory highlights that traumatic experiences can dysregulate the autonomic nervous system, leading to a chronic state of hyperarousal or hypoarousal. Individuals may become stuck in a heightened state of sympathetic activation (fight-or-flight) or a shutdown state (dorsal vagal), making it challenging to restore a sense of safety and regulation.

Regulated Nervous System

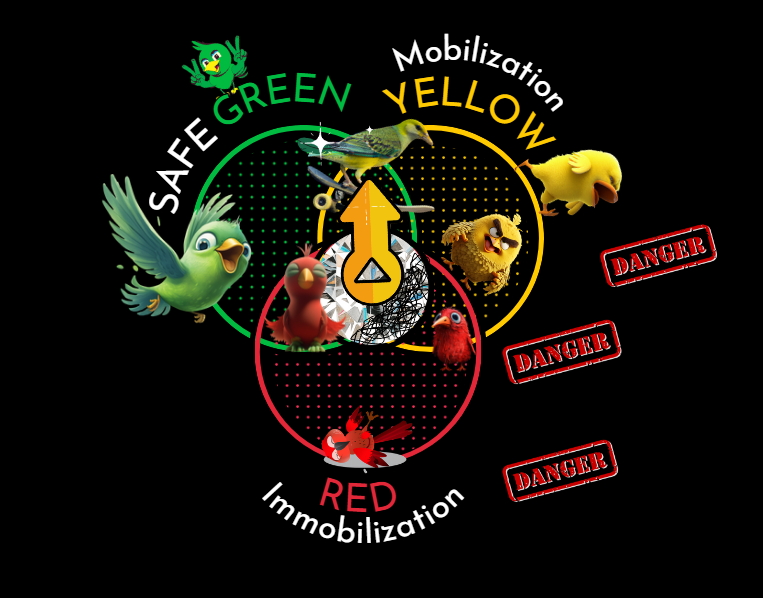

A regulated nervous system moves smoothly through the different polyvagal states as appropriate to the situation. This means it can adaptively respond to environmental cues and regulate its state accordingly. The 3 main states are:

- Ventral Vagal (GREEN): State of safety, social engagement, and calm.

- Sympathetic (YELLOW): Mobilization / fight-or-flight response.

- Dorsal Vagal (RED): Shutdown response.

In a regulated system, transitions between these 3 main physiological states are generally fluid and proportionate to the stimuli or situations encountered.

In contrast, a dysregulated nervous system experiences abrupt and disproportionate shifts, such as a sudden ‘elevator plummet’ from a state of calm (GREEN) to a state of high alert or activation (YELLOW) or even to a shutdown state (RED) without any objective threat present. This might happen due to past trauma, anxiety disorders, or other factors that sensitize the nervous system. Triggers are picked up behind the scenes (by the nervous system) and we can see a rapid shift the nervous system state.

These abrupt shifts can be disorienting and distressing, and they often don’t match the actual demands of the environment.

Interventions based on Polyvagal Theory aim to support individuals in regulating their autonomic nervous system responses, gradually restoring a sense of safety, and promoting resilience. These interventions may include practices such as grounding techniques, breathing exercises, movement, social engagement, and the cultivation of a safe therapeutic environment that supports co-regulation and the reestablishment of a balanced physiological state.

For more posts on polyvagal theory, click here

Recognizing Dysregulation

Recognizing a dysregulated nervous system can involve observing a range of physical, emotional, and behavioral signs. Here are some common indicators:

- Physical signs:

- Increased heart rate or palpitations

- Rapid or shallow breathing

- Sweating or clammy skin

- Muscle tension or tremors

- Digestive issues, such as stomachaches or nausea

- Fatigue or restlessness

- Difficulty sleeping or disrupted sleep patterns

- Emotional signs:

- Heightened anxiety or fearfulness

- Irritability or easily triggered anger

- Feeling overwhelmed or unable to cope

- Mood swings or emotional instability

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Hypervigilance or feeling constantly on edge

- Behavioral signs:

- Avoidance behaviors or withdrawal from social interactions

- Increased sensitivity to noise, light, or other stimuli

- Difficulty regulating emotions or emotional outbursts

- Impulsive or risk-taking behaviors

- Changes in appetite or eating patterns

- Increased use of substances (e.g., alcohol, drugs) as a coping mechanism

It’s important to note that these signs may not be exclusive to a dysregulated nervous system and can also be associated with various other conditions or situations. If you or someone you know consistently experiences these symptoms and they significantly impact daily functioning or well-being, it’s recommended to seek professional help from a healthcare provider or mental health professional for a proper evaluation and guidance.

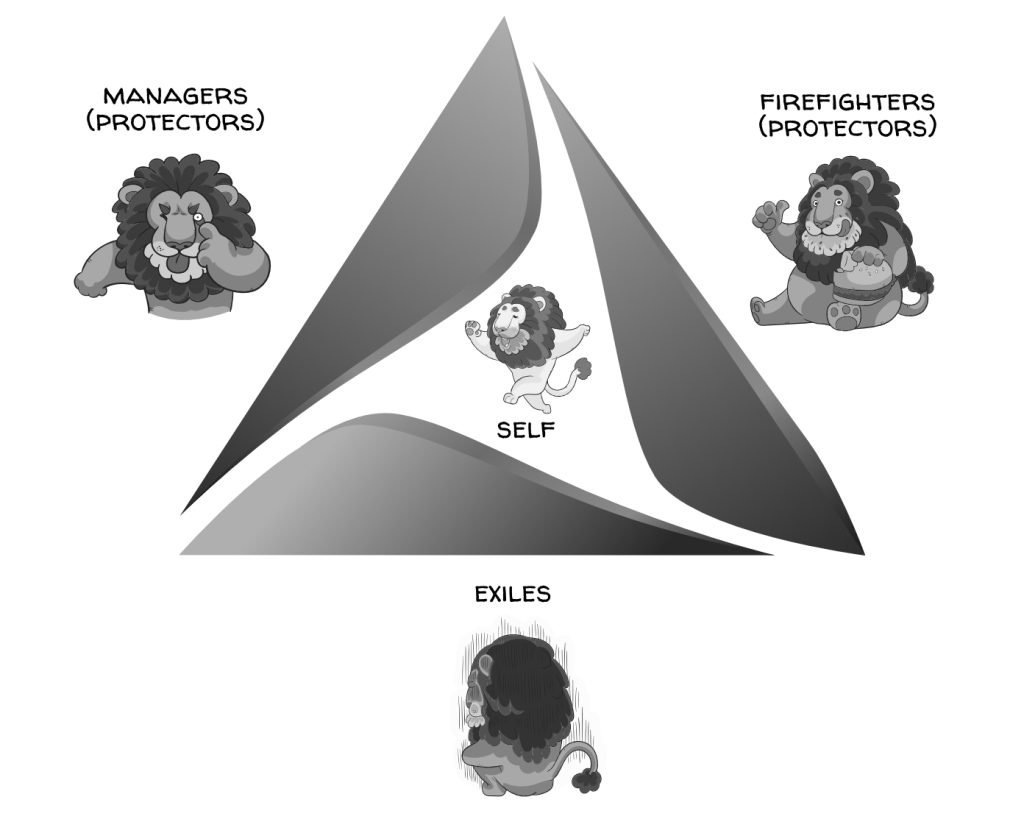

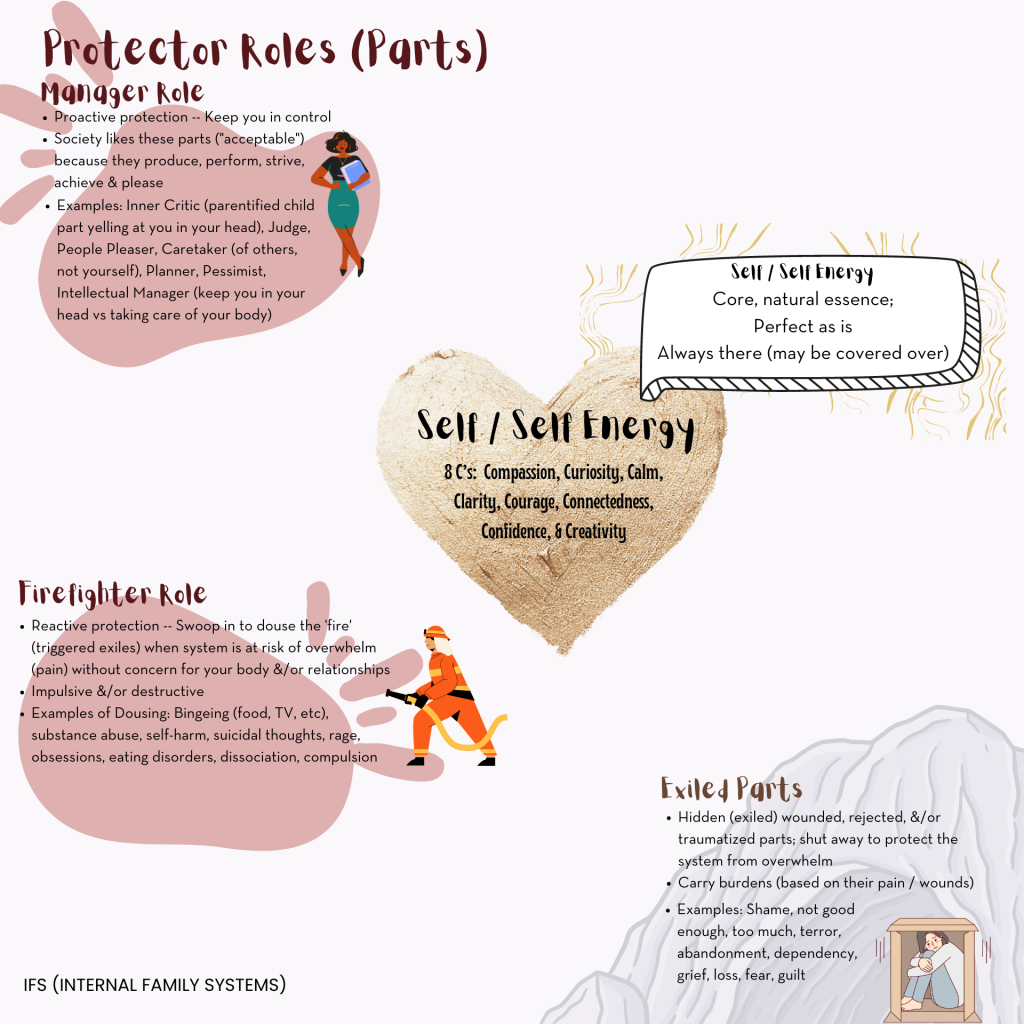

Using IFS to Recognize Parts and Self

According to the science-backed IFS Model (Internal Family Systems) proposed by Richard Schwartz, PhD we are not of monomind, but rather there is multiplicity of mind. We have parts. We are born with parts, and each part brings different resources to the table. We experience this day-to-day, and we say things like “Part of me wants ____, but another part of me thinks ______.” We truly have an internal family, and all parts have helpful intent. Trauma occurs when an individual experiences severe emotional or physical harm that exceeds their capacity to cope with the situation at hand. This often leads to parts jumping into action — taking on new roles, with the intent of helping the system. At the time of the experience, this new role may have been truly helpful and lifesaving. But as life goes on, these extreme roles may not be all that helpful. What this often looks like is an individual who has developed defensive mechanisms that aim to protect the individual from being overwhelmed by the pain of the past traumatic experiences. These defensive mechanisms are the action of protector parts. They seek to protect the system from getting flooded with pain. These parts may manifest as intense emotions, distressing memories, or reactive behaviors. Recognizing these parts and understanding their role can help identify the presence of trauma.

In IFS, trauma is often associated with the presence of exiles, which are wounded and vulnerable parts that have been isolated or suppressed as a result of traumatic experiences. The exile holds the pain of the trauma and, on top of that is now being hidden away (hence exiled) while carrying this burden of fear, shame, guilt, and/or despair. Exiles may hold memories, emotions, and beliefs related to the trauma. We see protector parts pop up, for example firefighter parts, which aim to distract, numb, or suppress the exiles’ pain — to keep that exile hidden away. These firefighters may manifest as addictive behaviors, dissociation, or other coping mechanisms. Recognizing the presence firefighters can be indicative of underlying trauma. Even suicidal parts have helpful intent — to keep that pain that the exile holds from flooding the system.

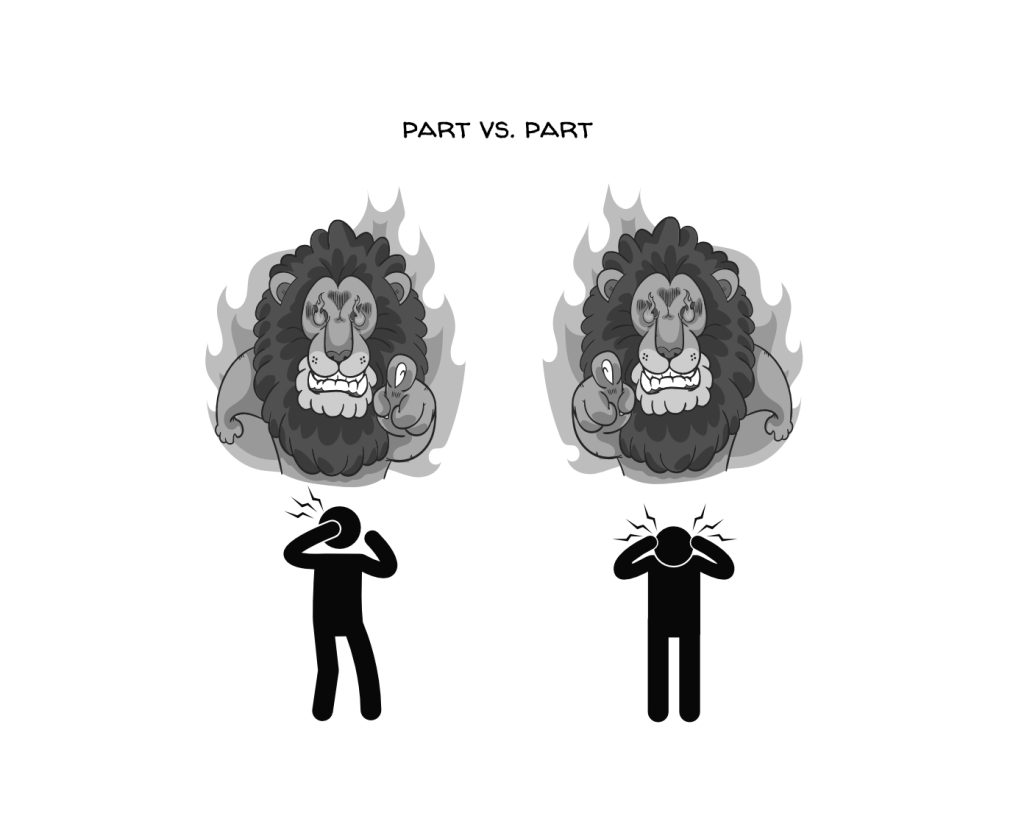

Trauma can create patterns of interaction between different internal parts. There’s that saying: A mind at war with itself knows not eternal peace. Parts can also be in cahoots with each other.

Another type of protector part we see is called a manager. Certain manager parts may indicate the presence of trauma. Manager parts in IFS are protective aspects of the internal system that aim to maintain control, avoid vulnerability, and prevent the reemergence of painful experiences. Here are some potential manager part roles that may suggest underlying trauma. This list is mean to be illustrative, not prescriptive:

- Hyper-Vigilant Manager: This part is constantly on alert, scanning the environment for potential threats. It may manifest as heightened anxiety, hypervigilance, or an excessive need for control. The hyper-vigilant manager may indicate a history of trauma where the individual learned to be constantly watchful and prepared for danger.

- Perfectionistic Manager: This part strives for perfection and imposes high standards on oneself and others. It may manifest as a critical inner voice, an obsession with details, or an intense fear of failure. The perfectionistic manager can be indicative of trauma where the individual learned to maintain control by seeking external validation and avoiding mistakes.

- Avoidant Manager: This part aims to avoid painful emotions, memories, or triggers associated with trauma. It may manifest as emotional numbing, avoidance of certain situations or topics, or a tendency to dissociate from present experiences. The avoidant manager attempts to protect the individual from overwhelming or retraumatizing experiences.

- Rationalizing Manager: This part uses logical reasoning and intellectualization to distance oneself from emotions or traumatic experiences. It may manifest as minimizing the impact of trauma, intellectualizing emotional experiences, or dismissing the need for emotional vulnerability. The rationalizing manager serves as a defense mechanism to maintain a sense of control and avoid overwhelming emotions.

To address trauma through the IFS Model, it is a multi-level, permission based process: all parts must consent. Typically the parts that you get to know would be: managers, then firefighters, and lastly exiles. Each step along the way achieves buy-in from all parts involved. If an individual has (or perhaps has) a diagnosable disorder, then IFS sessions are carried out by licensed professionals (e.g. a licensed therapist who is also IFS certified). If you are exploring IFS for wellness and resilience reasons, you can check out a free course here. There are also a lot of great IFS videos and meditations on YouTube, excellent books, etc.

This is a super quick nod to the IFS Model, but it’s important to comprehend how this model explains trauma as an experience that leads to parts taking on burdens and/or extreme roles. What we notice would be psychological symptoms and behaviors. To address trauma, the IFS model emphasizes the importance of compassion, empathy, and self-reflection towards the healing of protector and exiled parts. Once healed, parts can take on a more productive role in the system. WE can have true internal harmony — an inner fam led by Self (the part that’s not a part).

What happened to you?

When we truly realize what is going on with trauma physiology, we start to ask the classic question “What happened to you?” (versus “What’s wrong with you?”). We realize that the psychological and behavioral symptoms are parts in action.

This section is called Using IFS to Recognize Parts and Self because in the IFS model, the concept of Self is central. Self refers to a core, essential, and unburdened aspect of an individual’s inner being that possesses certain qualities and characteristics.

In the image below, the internal system of both parties are flooded with parts. Protector parts in each individual are being defensive and angry.

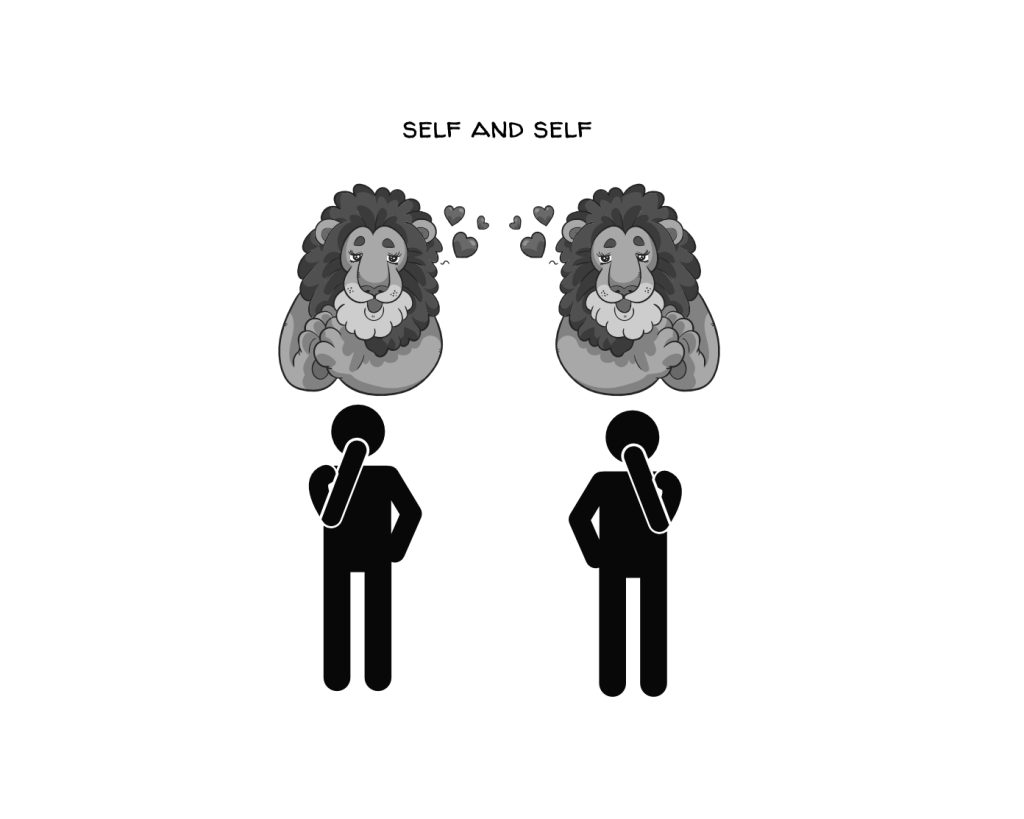

There are 8 qualities of Self called the 8 C’s, and these include calmness, compassion, curiosity, and connectedness. The Self is described as being grounded, compassionate, and non-reactive. It embodies a sense of curiosity, wisdom, and clarity. When individuals are connected to Self Energy, they can approach their thoughts, emotions, and experiences with a greater sense of openness and welcoming. Self is always present, but can be covered over by extreme parts. For people with severe trauma and mental disorders, they may be so disconnected from Self that they cannot access its energy, qualities, and wisdom.

In the image below, both parties are showing up with Self Energy.

Another important aspect of Self in the IFS model is its ability to provide healing, guidance, leadership to the various parts of an individual. How do you know if you are showing up with Self Energy? You can assess whether or not these 8 C’s are present.

The 4 R’s are quite a lot to take in, so let’s look at some of the key takeaways when it comes to the 1st two R’s:

- Trauma encodings are widespread; As trauma expert and pioneer Bessel Van Der Kolk explains notes “after trauma, the world is experienced with a different nervous system…every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past.”

- Trauma impacts the individual, social groups, and society; trauma is also passed down from generation to generation

- Trauma manifests as psychological and behavioral symptoms

- Burdened parts (parts that took on extreme protective roles as the time of trauma) have helpful intent; the “part that’s not a part” is Self/Self energy

- When we ask “What happened to you?” versus “What’s wrong with you?” we are really embodying realization when it comes to trauma and its effects.

- Understanding trauma physiology and the protective nature of parts can help us to be compassionate, curious and co-regulate those around us, vs getting activated ourselves. Check out the “When our calm meets their storm,” image in this post.

The Light Never Goes Out

This video is from the Superconscious Leadership perspective, where we acknowledge that “human being” can be considered as human (form) + being (formless). The biological spacesuit represents the form aspect: the physical, material aspect. The biological spacesuit is always adapting in helpful ways (at least the intent is helpful) to help to keep us alive. The light in the video below represents the formless aspect of us — the most foundational, perfect aspect. This would be equivalent to Self/Self Energy in the IFS Model. In DiSC DiSCO™, we call this the Omniversal Self. As we become more and more trauma-informed we better see the suit-stuff for what it is.

R#3 RESPONDS

Responding to Trauma: Leading with Awareness and Compassion

Responding to trauma within your work environment (or any environment) is about more than reacting to individual crises. It encompasses a comprehensive approach that weaves trauma-informed principles, policies, procedures, and practices throughout the entire organization. Leaders managing teams play a pivotal role in shaping the culture, performance, and well-being of their teams. Recognizing trauma and implementing measures to foster safety, empowerment, and collaboration are essential to a thriving workplace.

(1) Applying Trauma-Informed Principles

The program, organization, or system responds by applying principles of a trauma-informed approach to all areas of functioning. This recognizes that the experience of traumatic events impacts all people involved, whether directly or indirectly.

Key Principles Include:

- Safety: Creating physical and emotional safety is paramount. Leaders need to assess potential triggers and use de-escalation techniques where necessary. Regularly reviewing and implementing safety protocols and guidelines supports this process.

- Trustworthiness and Transparency: This involves clear communication, consistent schedules, inclusive language, and openness. Trust and fairness are nurtured through predictability and transparency in decision-making.

- Peer Support: Encouraging mutual, healing relationships among team members fosters a sense of community. Facilitating peer support groups or mentorship programs can be valuable.

- Collaboration and Mutuality: This principle emphasizes the flattening of hierarchical structures, giving all team members an active role in planning, evaluating, and decision-making. Let’s break this down:

Collaborate: To collaborate means to partner with others on a specific task or project, particularly with the intention of generating or creating something new. It’s about combining skills, ideas, and resources to achieve a common goal.

Mutuality: Mutuality refers to the reciprocal exchange of feelings, actions, or relationships among multiple parties. It’s the principle of shared experiences or common interests, where all parties are engaged in a way that benefits each other.

Collaboration and Mutuality in the context of trauma-informed leadership and organizational practice go beyond simply working together on a common task. They entail a synergistic relationship where all participants, regardless of their role or position, have an equal say and share in the responsibility. We foster trust and respect: Mutuality emphasizes empathy and understanding. Recognizing and honoring the unique contributions of each team member fosters trust and respect. It’s about creating an atmosphere where diverse perspectives are welcomed and appreciated, and where individuals feel seen and understood.

Collaboration is not a one-way street. It requires a reciprocal exchange of ideas, resources, and support. Mutuality, in this context, highlights the interconnectedness of all parties involved. It encourages a culture where help is readily given and received, and where successes and challenges are shared equally.

Collaboration and mutuality are not mere buzzwords but essential principles that foster a more inclusive, engaging, and productive work environment. They encapsulate the idea that every individual has something valuable to contribute, and that working together, with empathy and shared responsibility, can lead to greater success and well-being for all involved.

- Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: Leaders can foster empowerment by recognizing and building on individual strengths, encouraging resilience, and promoting shared goal-setting.

Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: A Deeper Look

Empowerment refers to the process of giving individuals the tools, resources, and confidence they need to take control of their own lives, decisions, and work. It’s about recognizing and building on their inherent strengths, abilities, and potential.

- In a Work Context: Empowerment involves delegating authority, offering opportunities for skill development, and encouraging employees to take ownership of their projects. It’s about creating an environment where people feel they have the power to make meaningful contributions.

- In a Healing Context: For those who have experienced trauma, empowerment may involve regaining control over one’s life and making decisions about one’s recovery and healing.

Voice is about giving individuals the opportunity to express their opinions, feelings, needs, and desires. It’s about actively listening and making space for diverse perspectives.

- In a Work Context: Voice involves creating channels for open communication, feedback, and dialogue. It’s about ensuring that all team members, regardless of their position, feel heard and valued.

- In a Healing Context: For trauma survivors, having a voice may mean being able to share their story, express their feelings, and articulate their needs in a safe and supportive environment.

Choice refers to the ability to make decisions and have options. It’s about autonomy and self-determination.

- In a Work Context: Choice can manifest in offering various paths for career development, project approaches, or problem-solving strategies. It’s about allowing team members to choose the methods and approaches that suit them best.

- In a Healing Context: For those healing from trauma, choice can be profoundly empowering. It might involve choosing one’s therapy approach, setting personal boundaries, or deciding how and when to share personal experiences.

Related to trauma, fostering empowerment, voice, and choice can be vital in supporting recovery and rebuilding a sense of control and self-worth. Incorporating the principles of Empowerment, Voice, and Choice in leadership and organizational practice contributes to a more engaged, motivated, and satisfied team. When team members feel empowered, have a voice in decisions, and can make choices, they are more likely to be invested in their work and committed to the organization’s goals. These principles foster a culture of creativity and innovation, as individuals feel free to think outside the box, express their ideas, and take calculated risks.

(2) Integrating Trauma-Informed Practices

Integrating trauma-informed practices requires concerted efforts across all levels of the organization. Examples of Integration Include:

- Ongoing Training: Regular workshops and training sessions ensure a consistent and empathetic approach.

- Intentional Policy Making: Including statements in mission statements or handbooks that reflect the organization’s commitment to trauma recovery.

- Fostering Safety: Leadership must ensure an environment that promotes trust, fairness, and transparency.

(3) Supporting Team Members

Providing support to those who may be affected by trauma is crucial. Considerations include:

- Promoting Choice and Collaboration: Offering options and shared decision-making can mitigate feelings of helplessness and promote empowerment.

- Understanding Physiological Responses: Familiarity with theories such as the Polyvagal Theory can guide leaders in supporting team members effectively. The Window of Tolerance and The Hand Model (Dr Dan Siegel) are also helpful options.

(4) Commitment to Healing

An effective response to trauma requires an expectation that trauma is a pervasive aspect of human experience and should not be replicated within the organizational environment. Leaders who demonstrate an understanding of and commitment to trauma-informed principles can foster a nurturing, productive, and empathetic work culture.

By wholeheartedly embracing this compassionate approach, leaders can help their teams not only function effectively but also thrive. This is not merely a change in policy but a transformation in organizational culture—one that acknowledges the profound impact of trauma and dedicates itself to healing, resilience, and growth.

Recall that this integration of trauma-informed practices needs to happen systemically, and be integrated with the Continual Improvement practice, Organizational Change Management practice, Knowledge Management practice, and more.

Responding to Trauma in the Workplace: Recognizing Signs of Trauma and Encouraging Support

As supervisors and co-workers, we are not qualified to diagnose mental health conditions like PTSD in our colleagues. However, there are some signs that could indicate an employee is struggling with an untreated trauma-related disorder:

- They share about experiencing a traumatic event like an accident, assault, or disaster.

- You notice ongoing symptoms like hypervigilance, avoidance behaviors, emotional numbing.

- Their work performance declines without explanation as they struggle with focus, motivation, or mood.

- They appear withdrawn, agitated, or exhibit worrisome shifts in demeanor.

If you observe persistent changes like these after an employee discloses a trauma, it’s appropriate to tactfully express concern and encourage seeking professional help. Avoid trying to diagnose them yourself. Instead, focus on the observable impacts:

- “I’ve noticed some changes lately and am concerned for your well-being. I want to help.”

- “Your performance seems affected recently. I suggest speaking to a counselor who can help you get back on track.”

- “It’s clear you’re going through a tough time. Please care for yourself and know our EAP offers resources and assessments.”

If work performance issues persist without improvement after encouraging the employee to seek help, it may be appropriate to loop in HR, while maintaining confidentiality. HR can assist with formal accommodations, leaves, or interventions while ensuring adherence to laws and company policies.

The goal is to convey care, note work impacts, suggest EAP counseling, and urge getting assessed – without overstepping your role. Ultimately, a mental health professional should determine if trauma responses meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD or related conditions. With sensitivity and compassion, supervisors can recognize signs of untreated trauma and encourage colleagues to access needed support.

R#4 RESISTING RETRAUMATIZATION

A Compassionate Approach to Healing and Growth

Re-traumatization is a profound risk, especially for those who have experienced previous trauma. It’s not just a concern in therapy or healing environments but can occur in workplaces, homes, and communities. The principle of resisting re-traumatization is an essential aspect of a trauma-informed approach, one that recognizes and seeks to minimize the risks, creating safe and supportive spaces. Re-traumatization refers to the process by which individuals are exposed to situations, behaviors, or environments that replicate aspects of their original trauma, causing the traumatic response to be reactivated. In simple terms, it’s a reawakening of old wounds, often unintentional but profoundly harmful. The challenge of resisting re-traumatization goes beyond the therapeutic context and extends to all environments, including workplaces, schools, and community organizations. It’s about creating a culture that recognizes the pervasiveness of trauma and actively works to prevent further harm. Strategies to incorporate:

Create Safe Environments

- Physical Safety: Ensure that spaces are designed with attention to potential triggers and provide areas for retreat or calming.

- Emotional Safety: Foster an environment where individuals feel secure in expressing their feelings, setting boundaries, and seeking support.

Empowerment and Autonomy

- Offer Choices: Providing options allows individuals to regain control, especially in situations where they may feel vulnerable.

- Foster Collaboration: Working together as equals can minimize power imbalances and encourage mutual respect.

Educate and Train Staff

- Understand Trauma: Staff at all levels should be educated about trauma, its impact, and how to avoid inadvertently causing re-traumatization.

- Provide Support: Regular supervision, guidance, and support can help staff navigate complex emotional terrain without causing harm.

Include Survivors in Decision-Making

- Seek Feedback: Those who have lived through trauma should have a say in how services or policies are designed.

- Value Experience: Recognize that lived experience is a form of expertise and can be invaluable in guiding best practices.

Resisting re-traumatization is not just about avoiding harm but about creating environments where individuals can grow, heal, and thrive. It’s about recognizing the inherent strength and resilience in each person and building on that to foster recovery and empowerment. By adopting the principles of safety, collaboration, empowerment, and inclusion, we can move towards a world where trauma is not only understood but actively mitigated. It’s a commitment to compassion, empathy, and respect, one that recognizes our shared humanity and the profound impact that our words, actions, and environments can have on each other. The 4th R of resisting re-traumatization is more than a principle; it’s a practice, a commitment, and a path towards a more compassionate and understanding society. Whether in a healing context, a workplace, or a community, it’s a vital aspect of creating a world that not only recognizes trauma but actively works to heal it.

4R’s Recap

SAMHSA provides a relevant framework for trauma-informed care through its 4 R’s:

- Realization – Recognizing the widespread impact of trauma and understanding it can have long-lasting effects mentally, physically and emotionally.

- Recognition – Identifying the signs and symptoms of trauma in individuals that may manifest in various overt or subtle ways. Being attuned to how trauma can present differently in different people.

- Response – Responding with trauma-informed principles and practices across the entirety of an organization or system. Creating a compassionate, empathetic environment that makes individuals feel safe, heard and understood.

- Resist Re-traumatization – Putting policies and procedures in place that aim to prevent re-traumatization. Fostering trustworthiness, collaboration and respectful communication. Emphasizing empowerment and choice.

The 4 R’s provide a comprehensive framework for what it means to apply a trauma-informed approach. It requires continual learning, reflection and a genuine commitment to nurturing environments for healing and growth. Each of the 4 R’s is essential and mutually reinforcing in supporting those impacted by trauma. By realizing, recognizing, responding and resisting re-traumatization, we can transform cultures and systems to be more compassionate, empathetic and sensitive to the diverse impacts of trauma.

Related Resources

More on “The Ladder” (The 3 states we covered plus blended states, eg sports and meditation)

Window of Tolerance (article with excellent graphics)

Window of Tolerance (PDF assessment)

Hand Model (for purchase on Amazon)

Polyvagal Flip Chart (for purchase on Amazon)

6 Guiding Principles to a Trauma-Informed Approach (CDC)

How Stress Affects the Brain (YouTube)

Responding to Stress and Dysregulation in our Nervous System (YouTube)

Relias has a lot of great resources, for example this video and slide deck

For regulation vs dysregulation, see Figure 2: Dynamic patterns of regulated and deregulated autonomic arousal. Adapted from Porges (1997)