Quality metrics are quantifiable values that measure a project’s performance against its quality targets: Based on the dimensions of quality that you are addressing, you will be monitoring the applicable metrics. PMI gives example dimensions of quality in the PMBOK 7:

- Performance

- Conformity

- Reliability

- Resilience

- Satisfaction

- Uniformity

- Efficiency

- Sustainability

Note that PMI.org defines quality as the degree to which a set of inherent characteristics of a product, service, or result fulfills the requirements. I have been teaching PMP Prep classes for a decade now and most students freak out when they see “relax a quality standard” as a possible tradeoff. They assume that we sacrifice quality, someone will die.

Yes, that can be the case: if we are making a medical laser, if we are off by a nanometer, that would be deadly. An aerospace turbine blade, might have a tolerance of ±0.005 mm to ensure it fits perfectly and operates efficiently under high stress. Get this wrong, and people can die.

But what if we are looking at the uniformity requirement for our RistRollers? In checking for uniformity, we are asking: does the deliverable show parity with other deliverables produced in the same manner?

We like to have the logo centered — exactly in the center. But will someone die if we are a nanometer off? A millimeter off?

Dimensions of Quality and Metrics (Example)

Performance: Metrics could include processing speed, system task completion time, or system uptime percentage.

Reliability: Metrics might be Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), uptime percentage, or incident frequency.

Conformance: This could be measured by the percentage of products or services meeting the standards or the number of non-conformance issues.

Durability: Metrics could include product lifespan, time to first maintenance, or number of repairs within a certain period.

Serviceability: This could be measured by average repair time, number of maintenance requests, or customer satisfaction with service.

Aesthetics: Metrics might include customer surveys on design satisfaction, number of design awards, or feedback on taste for food products.

Perceived Quality: This could be measured through brand reputation surveys, customer reviews, or net promoter score (NPS).

Lots of “-ities”

For other examples of quality requirements, you can peruse this Wikipedia entry, which outlines a long list of NFRs (nonfunctional requirements). Here’s an excerpt from this same wiki link:

Non-functional requirements are often called the “quality attributes” of a system. Other terms for non-functional requirements are “qualities”, “quality goals”, “quality of service requirements”, “constraints”, “non-behavioral requirements”,[3] or “technical requirements”.[4] Informally these are sometimes called the “ilities“, from attributes like stability and portability. Qualities—that is non-functional requirements—can be divided into two main categories:

- Execution qualities, such as safety, security and usability, which are observable during operation (at run time).

- Evolution qualities, such as testability, maintainability, extensibility and scalability, which are embodied in the static structure of the system.[5][6]

It is important to specify non-functional requirements in a specific and measurable way.[7][8]

Exception Plans

In the PMBOK 7, PMI describes the exception plan as the agreed-upon set of actions that we will take if a threshold is crossed or if we forecast that it will be crossed. Exception plans exist for quality, compliance, scope, costs, schedule, risks, etc. Examples of quality thresholds and planned responses could be:

Defect frequency exceeds 5% of total production → Initiate Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to identify the source of defects and implement corrective actions.

System uptime falls below 99.5% → Conduct a performance audit and optimize system processes to improve uptime.

Customer satisfaction score drops below 80% → Gather detailed customer feedback, identify key areas of dissatisfaction, and adjust processes or features accordingly.

Non-conformance issues exceed 2 per month → Review quality assurance processes, increase quality control checks, and provide additional training to staff.

In all of project work (and work in general) a scope of control is delegated downwards (control to act, make decisions, make tradeoffs, choose their way of working a.k.a. WOW, etc), with clear guardrails in place (the boundary of our power) and clear points of action/escalation.

The flow often looks like this: the team first investigates the issue and implements preventive or corrective actions if necessary (within their scope of control and take action per the exception plan). If the deviation persists or exceeds the team’s scope of control, the issue is escalated to the project manager (PM). The PM then performs a detailed analysis, and if the problem still cannot be resolved within their scope of control, it is further escalated to higher management or appropriate authorities to ensure timely and effective resolution.

PRINCE2’s Management by Exception empowers project teams while ensuring that they know when to escalate. This approach involves setting predefined tolerance levels for key aspects of the project, namely: time, cost, scope, quality, risk, and benefits. Project teams and project managers managers are given the authority to manage the project within established tolerances. If performance deviates beyond an established limits, it triggers an escalation process where the issue is reported to the next management level for intervention. This system allows for efficient project control, as it ensures that only significant deviations require senior management attention, thereby optimizing decision-making and resource allocation.

In project management, service management, etc, we see a cascade down of scopes of control (and more) and we see a cascade up when it comes to issues, risks, etc. that exceed our scope of control. You can think of management by exception as: I’m only gonna step in to exert management control when someone raises there hand.

Coming Up with Metrics

Per ITIL 4, controls are the means of managing a risk, ensuring that a business objective is achieved, or that a process is followed. Measurements are one of the most common types of controls, and ITIL breaks it down into 5 types of measurements:

- Progress measurements demonstrate the degree of achievement relative to defined

milestones and/or deliverables. - Compliance measurements demonstrate the degree of adherence to governance and/or

regulatory requirements. - Effectiveness measurements demonstrate the degree of fitness for purpose of any part

of the Service Value System (SVS), a product, or a service. - Efficiency measurements demonstrate the degree of fitness for use of any part of the

SVS, a product, or a service. - Productivity measurements demonstrate the throughput of a system (a value stream, a

process, a service, a component) over a period of time.

Many industries (and organizations) will have standard metrics in play.

Invoking Exception Plans / Escalation

We often see tolerance levels, which are gradated levels of tolerance to reflect minor, moderate, and major deviations, each with predefined actions and/or escalation paths. Below is a generic example.

- Target Level:

- Performance is within acceptable parameters.

- Action: Continue to monitor; no action required.

- Early Warning/Threshold Alert:

- Metrics are approaching predefined limits but have not yet crossed them.

- Action: Investigate the cause, prepare contingency plans, increase monitoring frequency. Handled at the team level via implementing the exception plan, likely involving preventative actions.

- Minor Deviation:

- Slightly outside the acceptable range but not critical.

- Action: Team-level response with corrective actions. Document the issue and resolution steps. Handled at the team level via implementing the exception plan, likely involving RCA and corrective actions.

- Moderate Deviation:

- More significant deviation that may impact project objectives.

- Action: Escalate to the project manager. Conduct a detailed analysis, implement corrective measures, and monitor closely. Exception plan likely specifies escalation to the project manager for detailed analysis and action.

- Major Deviation:

- Severe deviation that threatens project success or major objectives.

- Action: Escalate to senior management or the Project Management Office (PMO). Implement a comprehensive intervention plan, including root cause analysis and potentially revising project plans. Exception plan likely specifies escalation to senior management or the PMO for comprehensive intervention and decision-making.

Terms to Know – It’s Easier than You Think

In project management, familiar concepts can help us understand key terms. Think of “levels” like those in a Super Mario game – each level has its own rules, characters, and actions you need to take.

Similarly, project tolerance levels have specific criteria and related actions.

We have “limits” in life, like a credit card spending limit – a maximum you can’t exceed. We typically do not throw our hands in the air when this happens in real life, rather it’s a big deal to cross a tolerance limit, because it’s typically unacceptable to exceed a tolerance limit. (In the case of upper and lower tolerance limits, you wouldn’t want to exceed the upper, or come in under the lower.)

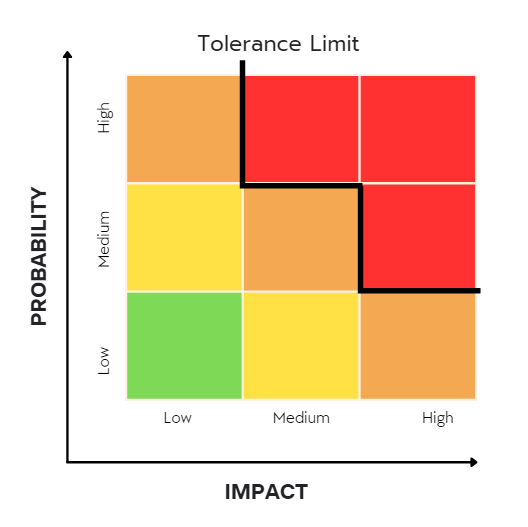

In project work there of often lots of tolerance limits being set at the start of the project (e.g. for quality, risk, etc.). For example, when analyzing a risk, we often score the risk based on PROBABILITY x IMPACT, calling this the risk score (RS), risk factor (RF), or magnitude. Our organization will likely have a max score (for risk) that its willing to accept. If we exceed the tolerance limit for risk tolerance, we don’t accept the risk. Period. (And your org is likely not going to let you sweet talk your way into changing this line in the sand.)

We see “thresholds” in real life, like the visible line in the doorway that’s called a threshold. In project work, a threshold is also a clear line: if you cross this line (or perhaps even if it looks like you’re going to cross it), a predefined action needs to be taken.

Best practice per PMI.org recommends using tolerance levels, exception plans, and escalation processes to systematically manage deviations in project performance. Tolerance levels gradate the variations (and related actions), exception plans outline actions to address deviations, and escalation ensures that critical issues/instances/items/exceptions are addressed by the appropriate authority. This structured approach helps maintain project control and ensures timely intervention when issues arise.

O.K. Now How You See it’s Easy, Here Are Some More Official Definitions

Tolerance: The quantified description of acceptable variation for a quality, risk, budget, or other project requirement (PMI.org). This always makes me think of a small child poking their older sibling. That sibling can only tolerate so much and then it’s: “I’M TELLING!!!!”

As a quality metric, if a part is specified to be 50 mm with a tolerance of ±0.5 mm, the actual dimension can be anywhere between 49.5 mm and 50.5 mm. Otherwise: I’m telling!

If you are addressing ±, you are probably talking tolerance.

Tolerance Limit: The specific boundary line that cannot be crossed. For example a risk tolerance line is literally indicated as a thick line on a probability / impact matrix. It represents the limit as to the level of risk the project owners are willing to tolerate for that project.

If you’re you have a line in the sand, beyond which whatever it is you are looking at is unacceptable, you are probably taking about a tolerance limit.

For quality tolerance limits, a great example is a control chart. We expect processes to have a certain degree of variation around a mean (average) value. but we have control limits so we can keep an eye on things, and then there are tolerance limits for the max value you can’t cross (upper tolerance limit) and the minimum value you can’t come in under (lower tolerance limit).

Crossing tolerance limits is unacceptable. But you may see the word “limit” used in other ways. For example, in manufacturing, for a component 1ith 10mm diameter:

Upper Control Limit (UCL): 10.05 mm

Lower Control Limit (LCL): 9.95 mm

Upper Warning Limit (UWL): 10.03 mm

Lower Warning Limit (LWL): 9.97 mm

Upper Action Limit (UAL): 10.06 mm

Lower Action Limit (LAL): 9.94 mm

The lines that you can’t cross might be:

Upper Tolerance Limit: 10.06 mm

Lower Tolerance Limit: 9.94 mm

Threshold: A predetermined value of a measurable project variable that represents a limit that requires

action to be taken if it is reached (PMI.org).

When it comes to a dimension of quality, this would be a predefined point at which specific actions or responses are triggered; we’d use this threshold in quality control and exception planning. For example, if the defect rate in a production process exceeds a 2% threshold, an investigation and corrective action must be initiated.

Just like you can walk through one door and then another and then another, a threshold is a line, that if you cross, you need to take certain action. (Note how this definition is less dramatic than the definition of a tolerance limit.)

Tolerance Levels: The gradated ranges variations within which a project or its deliverables, e.g.:

- Target Level: The optimal performance or measurement where everything functions perfectly.

- Early Warning Level: A range indicating that performance or measurements are approaching unacceptable limits and may need attention, as defined in an exception plan. For example, the team can typically address issues at this level.

- Severe Warning Level: A range indicating that performance or measurements are approaching critical limits and may require escalation to higher authority, as outlined in the exception plan.

- Failure Point/Level: The point at which performance or measurements exceed acceptable limits, requiring immediate corrective action, as defined in the exception plan. This would likely be the point of escalation to a higher authority and is often the tolerance limit.

Exception Plan: An agreed-upon set of actions to be taken if a threshold is crossed or forecast (PMI.org). These plans ensure that deviations are managed systematically to bring the project back on track. This plan will tell you when exactly to take certain actions (actions YOU should take) and when exactly to raise your hand/escalate (so the appropriate party can act). Cross this line, do this… Cross that line, do that. Cross this other line, well now you need to escalate.

Escalation: The process of raising an issue to higher management or another authority when it exceeds the project manager’s ability to resolve it within the established tolerance levels. This ensures that critical issues receive the necessary attention and resources.

Examples of Tolerances and Thresholds

ISO 2768-1: This is the industry standard for determining general tolerances for linear and angular dimensions, as well as for features such as radii and flatness. For example, a part might have a tolerance limit defined by ISO 2768-1 as fine (f) for metals, which can be as tight as ±0.05 mm (50 microns), or medium (m) for plastics. This standard ensures that CNC machining operations can consistently achieve high precision without needing detailed specifications for every dimension.

LEED Certification: In sustainable building practices, LEED sets thresholds for various environmental factors. For example, the volatile organic compound (VOC) content in paint must be below a specified limit, such as 50 grams per liter. If we come in below this threshold, the building qualifies for LEED points toward certification. Cross the line and you fail to receive the points.

Six Sigma: In quality management, Six Sigma aims for no more than 3.4 defects occur per million opportunities. This high standard means processes must be extremely consistent and within very tight tolerance limits to minimize variation and defects.

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: To ensure accuracy and safety, perhaps active ingredient concentration in a medication must be within 98% to 102% of the labeled amount.

Key Points:

Thresholds:

- Action-Oriented: Each breach comes with a specified action, ensuring timely and appropriate responses.

- Multiple Levels: Different thresholds can be set for various levels of severity, allowing for a graduated response.

- Proactive Management: Helps in identifying and addressing issues before they escalate to critical levels.

Tolerance Limits:

- Absolute Boundaries: Represent the maximum allowable deviation (eg you may see 1 tolerance limit as in for risk, and you may see upper and lower tolerance limits for quality).

- Critical Decision Points: Crossing a tolerance limit often requires significant intervention, such as project re-evaluation or termination.

- Risk Management: Essential for managing high-stakes elements of the project, such as budget, schedule, and scope.